COA instruments that are relevant to patients typically center around three factors that impact their quality of life while on a medication:

- Symptoms: Does the drug lessen the disease burden by eliminating or mitigating complications such as pain, fever, a lump or bump, or difficulty sleeping?

- Functions: Does the drug allow them to participate in activities of daily life when they otherwise could not?

- Intrusiveness of medication: Does the drug involve intrusive administration paraphernalia (bulky inhalers, injector pens, or hospital visits), monitoring procedures (lumbar punctures or serial blood tests), or side effects?

Sponsors often overlook intrusiveness when selecting COAs, but it is central to patients’ decision-making. Some sponsors are so focused on proving whether a drug works at the cellular level or is compliant with good manufacturing practices (GMP) that they forget how intrusive it may be in a patient’s everyday life. For example, inhaled insulin was hailed as a breakthrough for diabetes patients, and more convenient than subcutaneous insulin delivery. However, various side effects, medical insurance hurdles, and the fact that existing pen syringes and needles are almost painless for most diabetics, hampered uptake.³

Sponsors must balance time and cost when incorporating patient perspectives, but if they fail to submit adequate evidence of a drug’s impact on patient-relevant outcomes, their products could fail when challenged by regulators, HTA reviewers, and payers.

To convince HTA agencies and payers, sponsors increasingly need to submit quality-of-life evidence to support pricing. Before they make an expensive new product available, they demand compelling data on patient benefits. It is important to carefully select COAs that—when measured adequately—reflect an aspect of health that is important to patients, can be modified by the investigational treatment, and could demonstrate clinically meaningful differences between study arms within the time frame of the planned clinical trial.

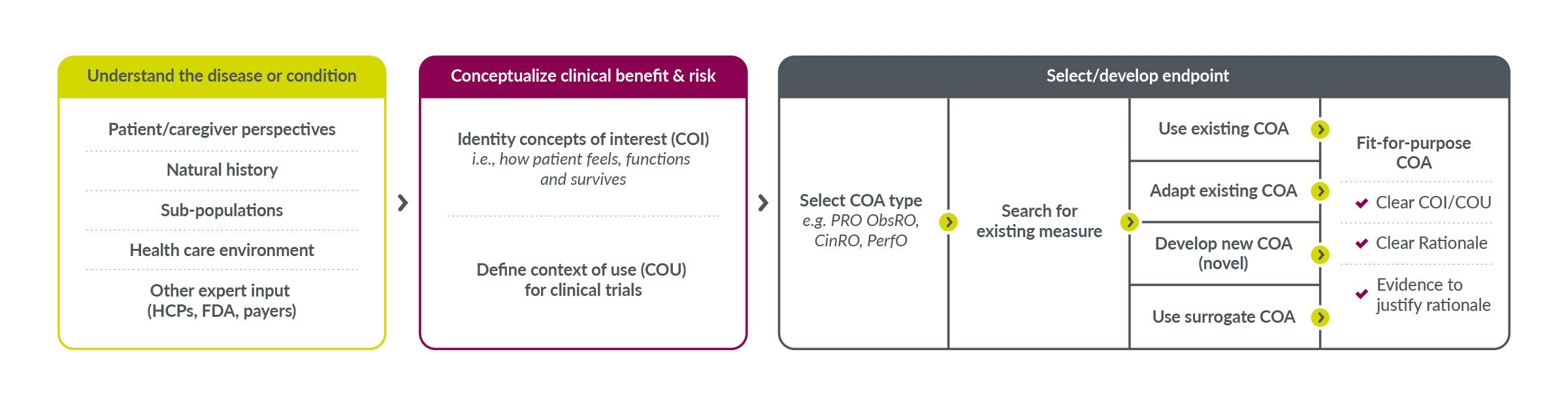

Ensure COAs are fit for purpose

At Parexel, we apply key performance indicators (KPIs) to new or existing COAs to determine if they are fit for purpose. Sometimes we find an existing COA that works or can be modified. Other times it is necessary to develop a wholly new COA or combine elements of existing ones into a new measure. When we determine that a COA is critically flawed, we move on and find better ones.

Some COA instruments are flawed because they are difficult for patients to understand. For example, one commonly used PRO tool to measure patients’ “satisfaction” with a treatment begins with a convoluted question: “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the ability of the medication to prevent or treat your condition?” Patients are then supposed to rank their satisfaction on a scale of seven, from “Extremely Dissatisfied” to “Extremely Satisfied.” This is not intuitive and was not developed with patient input. An alternative PRO asks simpler questions such as “The side effects of the medicine interfere with my physical activity (e.g. lifting, walking, jogging, etc.).” Then patients can choose five answers from “Not at all” to “Very Much.” Patients contributed to the wording used in the second tool.

Key performance indicators (KPIs) can help companies select patient-relevant COAs

| Key KPI |

Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) or Observer-Reported Outcome (ObsRO) |

Clinician-reported Outcome (ClinRO) |

Performance Outcome (PerfO) |

| Patient Relevance |

Has it been developed with patient and caregiver input? |

Has it been developed with patient and clinician input? |

Can it be performed by the patient? |

| Burden Time for Administration |

Does it take longer than human attention spans? |

Does it require limited clinician training and recalibration? |

Is the performing test time causing pain? |

| Interpretability |

Is the score relevant to patients? |

Is the score relevant to clinicians and patients? |

Is the score relevant to patients and testers? |

| Readability and Complexity |

Can patients understand the questions? |

Can clinicians understand the instructions? |

Is the task ecologically valid? |

| Cross-Cultural Validity |

Is the concept valid in all countries? |

Is the clinical test used in the medical schools of the countries? |

Does the performance test work in all countries? |